When I sat down to hear Elvis Obi’s story, the Nigerian designer, now design leader, I knew the first thing I wanted to understand wasn’t about design, gaming or building the videogame company, Mazerance

It was about money.

How does someone with a degree in biochemistry, who once lost jobs in toxic workplaces, go from surviving on small freelance gigs to running a game studio that pays salaries in thousands of dollars?

This is a story l wanted to hear and learn a thing or two, and we started from the beginning.

The Beginning

Growing up as the second of five children, his strongest suits were drawing and writing. A pivotal moment came in primary school when he won first place in a regional Spelling Bee, an experience that involved intense training in etymology and ignited a deep love for language.

This passion carried into university, where he studied Biochemistry, a path chosen after several unsuccessful attempts to study Medicine. Despite his science major, his creative spirit led him to the school’s writers club, where he became a spoken word artist, overcoming stage fright and building foundational public speaking skills. He also began creating biblical comics, which led him to teach himself the principles of design in 2016 before diving into Adobe Illustrator, Photoshop, and CorelDRAW.

When Elvis graduated in December 2019, he fell back on what he had always been good at, writing.

Copywriting, technical writing, even social media management. His early projects with firms in New York and South Africa brought him $1000 here, $2000 there. Not life-changing money, but it felt like survival income, but also a proof he could get paid for his skills.

But the truth? The money wasn’t enough to build a life.

One of those roles involved creating pitch decks for a church software product during COVID-19. The product never took off, and the company in South Africa let him go. “That was my first lesson,” he says. “You can give your all, but if the money isn’t flowing into the company, you’re disposable.”

The paychecks stopped. The bills didn’t.

The Pivot to Design

Fired, broke, and frustrated, Elvis turned to something new: design.

It was during this time that he had his first exposure to UX design. “I always found it quite fascinating that people design these screens… I felt like maybe it was the role of the engineer to design and implement. I didn’t know designers were also involved in the process.”

With encouragement from a friend, he opened Figma and began a routine that looked less like casual learning and more like obsession. Eight hours a day, sometimes more.

The Big Break

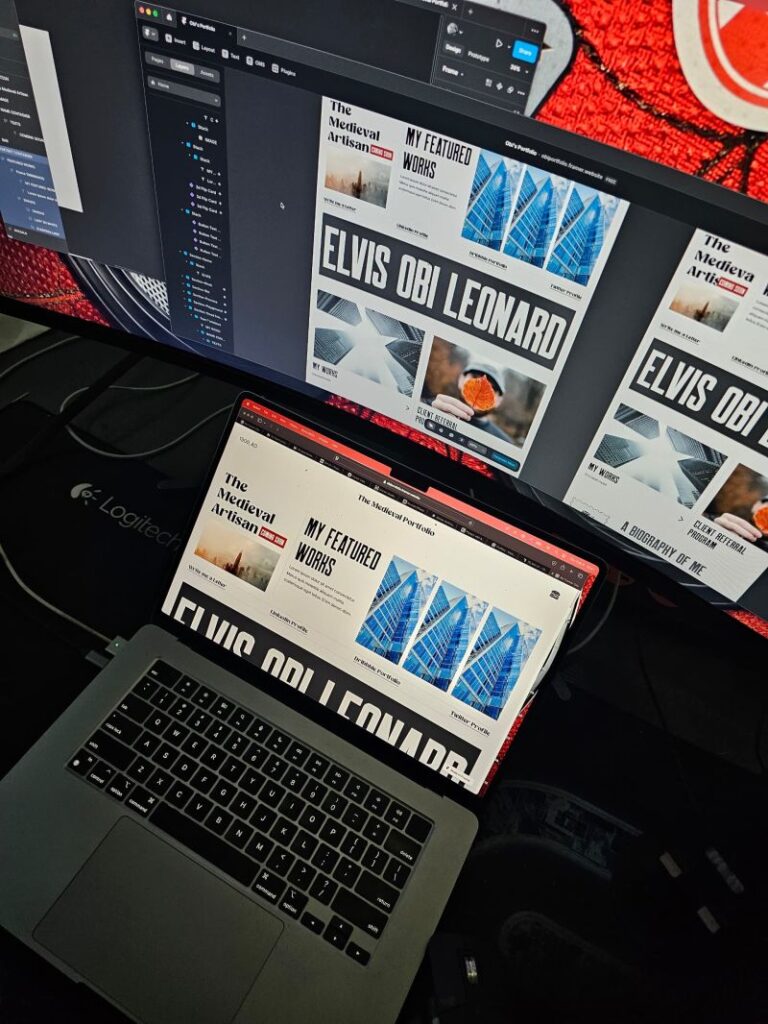

After two months of intense, eight-hour-day mentorship, his dedication paid off. He completed a project for a client who loved the work. Emboldened, he designed a concept for a product called “Rating,” a platform for reviewing Nigerian companies.

He posted it on Twitter and LinkedIn on January 14th, 2021. It went viral. “Over 2 million people saw it… a lot of people and companies reached out to me. And that’s basically how my design career started.”

Elvis’ career is marked by a firm understanding of his value and a low tolerance for professional disrespect. He shared another experience where he was fired for standing up for a senior designer who was let go unjustly. This principle led him to be cautious about his next role.

When a Nigerian fintech reached out, he took three months to accept the offer. “I told myself that whatever company I’m joining next, I want to stay… for at least two to three years.” He stayed with them for two years, serving as the sole designer, maintaining and evolving their design system and focusing primarily on B2B and corporate dashboard products, calling it “one of the best places I’ve worked at.”

The Bigger Money Lesson

Elvis admits he didn’t always handle money well.

“I remember once earning about $15,000 from different gigs in a single month. I felt rich. I changed my wardrobe, gave people money, and spent extravagantly. And then, in weeks, it was all gone. That’s when it hit me, you can earn well and still be broke if you don’t plan.”

That lesson followed him into the following things he did next: always tying money to intention. If he worked, he asked: what’s this for? Growth, stability, or just survival?

From A Talent To A Leader

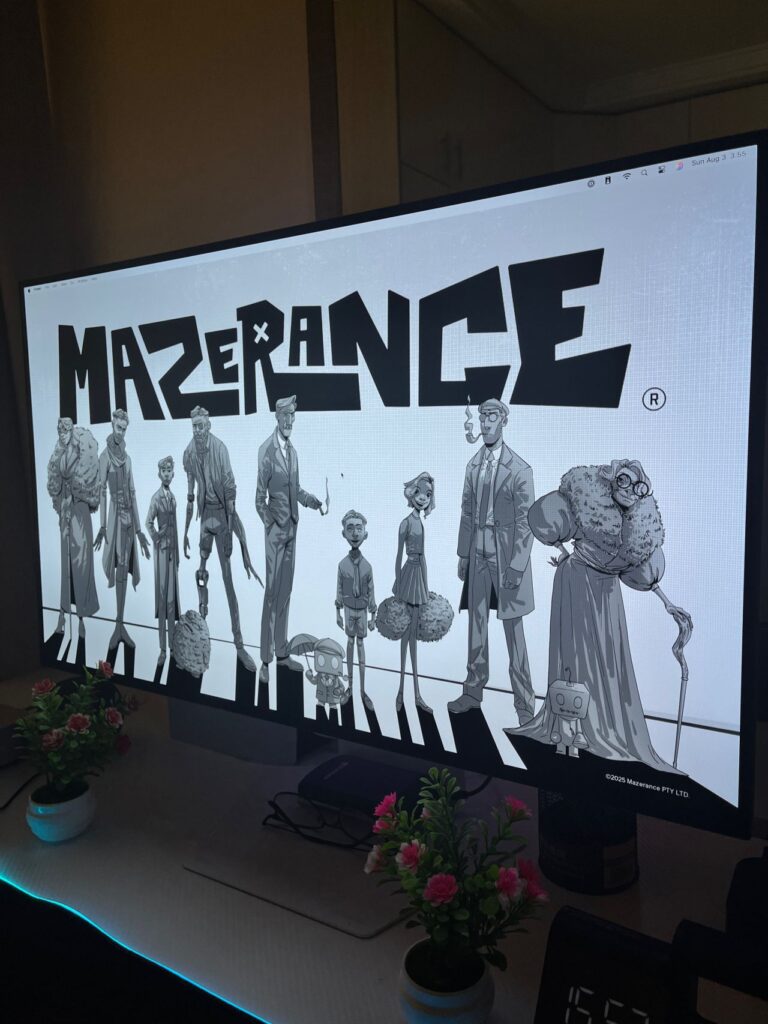

Elvis is building his most ambitious project yet: Mazerance, a video game company, by Five Blooded, a multi-studio studio based in Australia. The name itself, a portmanteau of “maze” and “severance,” hints at its conceptual depth, inspired by the enigmatic TV show but crafted with a completely unique identity and purpose.

But for Elvis, Mazerance is beyond a creative venture; it’s a radical operational experiment. It was built as a direct rebuttal to the exploitative environments he had endured. Unlike his early jobs where salaries were withheld and expenses came from his own pocket, Mazerance was engineered from the ground up to value and compensate talent fairly.

“People think you can’t pay Africans well because the exchange rate makes it ‘expensive,’” he explains, challenging a common justification for low pay. “But if you want world-class talent, you must pay world-class rates. Otherwise, they’ll leave for companies abroad. We have some of the best African talents working with us precisely because we pay well.”

This philosophy is alive in the company’s structure. Today, Mazerance is a company of 26 artists, engineers, and designers hailing from Nigeria, Ghana, Singapore, Senegal, and beyond, with plans to hire talent from Canada, Brazil, and the US. The pay scale is a testament to its commitment: junior roles start around $700+ a month, while specialized, advanced roles, particularly for rare skills like C++ programming crucial for game development earn as much as $5,000+ per month.

Elvis is blunt about the reason for these rates: the work is exceptionally difficult. He classifies game development as “the pinnacle of software engineering,” more complex than standard front-end or app development due to its reliance on intricate languages and 3D modeling. This complexity, combined with a desire to “redefine what quality is for a product built by Nigerians,” justifies the investment. The goal is not just to compete locally, but to create a product whose quality is undeniable on a global stage, aiming for a player base primarily outside of Africa, and Australia (where the company is registered.)

For Elvis, Mazerance is the ultimate proof of concept. It’s a living, breathing argument that Nigerians can not only dream on a global scale but can also operate at that level, building rigorous, flexible, and autonomous work structures while paying salaries that attract and retain top-tier international talent. It’s about proving that with the right backing, intentionality, and respect for creators, the next wave of African innovation can extend far beyond fintech and into the vast, imaginative realms of worlds yet built.

Money as Freedom

Elvis now leads a design team at Mazerance, and the difference between his early career and now is night and day.

Back then, money felt like survival. Scraping together a few hundred dollars, hoping it stretched. Now, money feels like freedom. The freedom to hire. The freedom to retain talent. The freedom to experiment and still keep the lights on.

Mazerance already has plans to present at a major gaming conference in Germany, a stage usually reserved for American, European, or Asian studios. Elvis wants his team, many of them Nigerians to stand there proudly, knowing they’re being paid fairly for world-class work.

But the hardest part isn’t the money itself. It’s explaining the vision to his team of 25+. “Convincing them that we’re not just building a game for fun, but building a company that can shift culture, that’s harder than fundraising.”

When I asked Elvis what surprised him most about his money moves, he didn’t hesitate.

“How easy it is to underestimate yourself. I used to think $5,000 was good money until I realized my work could bring in $500,000 for someone else. That’s when I stopped playing small.”

I’ve lived many lives, but one lesson ties them all together: money is only as powerful as its utility. Through my work, I share stories about money and create guides for Africans who want to get the best out of theirs.